In 2024, Mauritius introduced the Corporate Climate Responsibility (CCR) Levy, a landmark policy to align private sector profitability with national climate resilience.

For a small island developing state economy exposed to escalating climate risks, this measure marks a decisive shift: climate resilience becomes a shared balance-sheet issue for the State and the private sector.

This levy has come about as a response to the escalating climate disruptions that Mauritius has been facing over the past few years. As a tropical island, Mauritius has long been susceptible to cyclones, floods, and heavy rainfall. The Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance Climate reports annual economic losses estimated at USD 110 million, of which cyclones account for 80% and floods 20%.

In recent years, urban expansion in flood-prone areas has intensified these risks, resulting in tragic events such as the 2013 Port Louis flash floods which claimed 11 lives, and Cyclone Belal in 2024, which caused widespread damage across the island. The World Risk Report 2025 ranked Mauritius 106th out of 193 countries for vulnerability to climate disasters.

To address this, Mauritius took several measures to strengthen its climate governance architecture. Legislation such as The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act 2016, which created a National Disaster Management framework, and The Climate Change Act 2020, which established institutions such as the Department of Climate Change and the Inter-Ministerial Council on Climate Change, were put into place.

In 2016, Mauritius ratified the Paris Agreement on climate change and, as part of its required nationally determined contributions, Mauritius committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2035 which requires an estimated USD 11.3 billion in climate financing between 2026 and 2050. The CCR Levy represents a blended financing strategy to achieve this.

The CCR Levy is imposed under the Income Tax Act. It consists of a 2% levy on a company’s chargeable income (profits) for entities with an annual turnover exceeding MUR 50 million.

For the purposes of the CCR Levy only, the Income Tax Act extends the definition of turnover to include all gross income, even traditionally exempt revenues such as dividends and capital gains. This broader definition limits base erosion and ensures contributions from capital-light sectors, notably finance and global business. This, in turn, reduces distortions across sectors, especially where emissions accounting is difficult.

The CCR Levy applies to all tax-resident companies in Mauritius, including:

- Global Business Licence holders;

- Protected Cell Companies and Variable Capital Companies; and

- foundations, trusts, and sociétés (which are included in the definition of ‘company’).

A resident société is expressly brought within scope and is treated in the same way as a company for CCR Levy purposes. Its net income is deemed to be its chargeable income for calculating the levy.

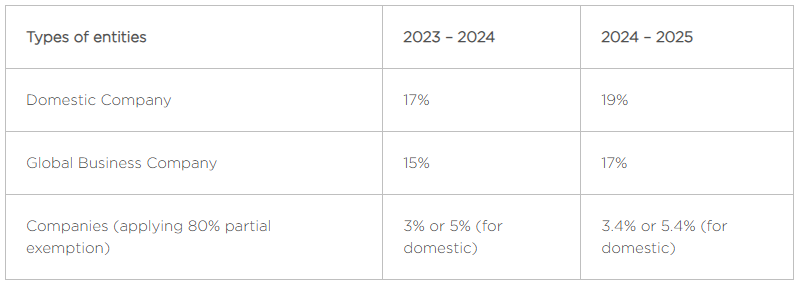

While the 2% rate may appear modest, its impact is amplified for firms under certain exemption regimes, as shown in the table below.

In practice, effective rates rise most for firms using partial exemptions, tightening the spread between low- and standard-taxed activities. This of course impacts competitiveness, especially in globally integrated sectors.

The CCR Levy has now been in force for one full year, effective for years of assessment beginning in July 2024. Despite calls, particularly from global investment structures, for carve-outs or narrowed scope, the Government that took office in January 2025 has not signalled any intention to curtail the levy’s application.

This is in some measure due to the fact that the levy also presents an opportunity for firms to realign their sustainability strategies. In order to mitigate the impact of the levy, companies are adapting to this neo movement by leveraging foreign tax credits and green investment incentives.

Learning from international firms that align CapEx with decarbonisation, which often result in lower cost of capital and improved insurer terms, companies in Mauritius recognise that they can offset levy exposure by accelerating energy efficiency, electrifying fleets, and issuing sustainable bonds; actions that can qualify for incentives and reduce operating costs.

The levy proceeds flow to a newly established Climate and Sustainability Fund (Fund), managed by a joint public-private committee, which will support projects focusing on:

- climate adaptation and mitigation;

- ecosystem restoration;

- renewable energy transition; and

- sustainable land and coastal management.

The Fund is open to contributions from international partners and individuals. A good way to boost this structure would be to attract private co-investors by publishing an annual impact and allocation report, adopting transparent project selection criteria, and ring-fencing proceeds by program, with independent audits.

In parallel, Mauritius has been developing an enabling environment for green capital and corporate transition. In 2021, The Bank of Mauritius issued a Guide on Sustainable Bonds to promote responsible financing and prevent greenwashing.

It also established a Climate Change Centre to develop environmental risk data and promote sustainable banking practices. In the same year, the Financial Services Commission published its guidelines for the issuance of corporate and green bonds, elaborating on the regulatory requirements to be adopted by the issuers of ‘Green Bonds’ in line with international best practices.

CIM Financial Services Ltd issued the first Green Bond of Mauritius in January 2022. The funds raised were aimed at financing the company’s Green Lease product, meant to encourage the shift to hybrid and electric vehicles, as well as supporting any other green projects undertaken by Cim Finance’s clients.

In 2025, CIEL Ltd successfully completed the issuance of MUR 1.45 billion (USD 31 million) sustainability-linked bonds, in line with its commitment towards sustainability objectives, namely promoting women empowerment, reducing its carbon footprint and cutting water consumption. This marked a first in Africa for a diversified investment holding company, with foreign investors, through the Africa Local Currency Bond Fund, participating in the Mauritian local currency debt capital market.

On an international level, various countries have adopted fiscal and regulatory tools to internalise the cost of environmental degradation and drive low-carbon transitions.

Countries like Sweden and Canada impose direct taxes per tonne of CO2 emissions, creating strong incentives for emission reduction. South Africa introduced a carbon tax, in 2019, applicable to large emitters, with incremental increases scheduled to strengthen its effect. In Europe and UK, the Commission Implementing Regulations (ETS) employ a cap-and-trade model, allowing companies to buy and sell emission allowances, thus pricing carbon in a market-based framework. Germany taxes electricity and petroleum consumption but offers tax relief for renewable energy use. Countries such as Canada tax fuel-inefficient vehicles, and several EU states impose airport and fuel levies earmarked for environmental projects.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms ensure that imported goods reflect the carbon costs borne by EU producers, reducing ‘carbon leakage’ and encouraging global adoption of carbon pricing. For Mauritius, the approach is not to replicate high-complexity ETS systems but to adopt fit-for-purpose pricing plus incentives that are administratively feasible and trade-aware.

Against this backdrop, Mauritius’ CCR Levy stands out as fundamental shift in fiscal policy where taxation becomes not only a tool for revenue generation but also an instrument to drive sustainable transformation. By taxing profits rather than emissions, it provides a practical approach for a small economy with limited industrial data and administrative capacity. It also reduces measurement burden and captures risk for services-heavy sectors while still mobilising climate finance.

It is to be noted, however, that these measures represent negative pricing instruments designed to discourage environmentally harmful behaviour through prohibitions, penalties, or financial disincentives.

As the climate crisis intensifies, this approach alone appears insufficient to drive the systemic transformation. Complementary incentive-based measures (for example, targeted capital allowances for energy efficiency, accelerated depreciation for clean tech, green credit guarantees, and customs fast-tracks for low-carbon equipment) that encourage positive environmental action through rewards, recognition, or support are equally essential to ensure that individuals and businesses are not only held accountable but also empowered to innovate sustainably.

Many countries have adopted climate strategies that increasingly reflect a balanced framework complementing fiscal measures with regulatory, social, and technological initiatives aimed at reinforcing climate resilience.

New Zealand’s Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 introduced legally binding emissions budgets and created the Climate Change Commission to provide expert advice and monitoring to help keep successive governments on track to meeting long-term goals. Singapore’s Green Mark Certification Scheme, launched by the Building and Construction Authority of Singapore in 2005, is a green building rating system designed to evaluate a building’s environmental impact and performance and aims to promote best practices in construction and operations in buildings such as encouraging low-energy design and materials and more sustainable buildings.

The Energy Transition Law’s Article 173 in France, provides that certain firms are legally required to publish their carbon footprints and mitigation plans. The United Arab Emirates has put in place the national Net Zero by 2050 Strategy, focusing on renewable energy, low-carbon buildings and innovation in urban development, notably in Masdar City.

Across these systems, three success factors recur: predictable policy signals, credible disclosure regimes, and investable project pipelines. Mauritius is fully capable of adopting these same principles, without necessarily importing their associated administrative complexities.

While each of these measures differs in scope and design, together they illustrate how diverse tools are being mobilised globally to reinforce climate resilience. In Mauritius, several renewable energy and efficiency initiatives have been initiated in recent years:

- Renewable Energy Transition: In 2019, the Government put in place a Renewable Energy Roadmap 2030, with a long-term energy strategy target of 35% renewable energy in the national mix, which was subsequently revised to 60% in 2022. In the 2025/2026 National Budget, investments in solar and wind projects, battery storage, and waste-to-energy initiatives were announced, echoing the consistency and continuity in the Government’s attention to climate change regulation despite a change in the ruling political party.

- Coastal and Biodiversity Protection: Initiatives such as coral reef restoration, mangrove rehabilitation, and coastal zone adaptation projects are supported by local non-governmental organisations and international partners. The governments of Mauritius and Seychelleshave recently been granted USD 10 million from the Adaptation Fund through the United Nations Development Programme in a six year project called ‘Restoring marine ecosystem services by restoring coral reefs to meet a changing climate future’ which will develop sustainable partnerships and community-based, business-driven approaches for reef restoration and the establishment of coral farming and nursery facilities. The second phase of the SOS Mangrove Programme, first initiated by Reef Conservation, following the oil spill of the bulk carrier MV Wakashio off the coast of Mauritius, is now being funded by the MOL Mauritius International Fund for Natural Environment Recovery and Sustainabilityto bridge knowledge gaps on Mauritius’s mangrove ecosystems, raise public awareness, and establish a permanent mangrove nursery. This fund was established in Japan by Mitsui O.S.K Lines Ltd as part of benevolent and philanthropic actions to support environmental initiatives and community strengthening projects.

- Public Education and Policy Integration: Environmental education has been integrated into school curricula, while green public procurement policies encourage government agencies to adopt sustainable practices.

- Climate Finance Management: A Climate Finance Unit is projected to be set up at the Ministry of Finance to better mobilise and manage climate finance for adaptation, mitigation and resilience.

However, progress has been relatively slower compared to that in other countries. Various institutional and operational factors have contributed to delays in the implementation of these projects. For instance, the activities of the Mauritius Renewable Energy Agency and the Energy Efficiency Management Office, both established to support the national clean energy transition, have not advanced as originally envisaged. A pragmatic delivery plan, standardised PPAs, grid investment scheduling, and a one-stop project preparation facility could, in fact, accelerate execution within existing institutions.

It is undeniable that an approach blending continued institutional development, ongoing investment in climate resilience, fiscal innovation, regulatory reform, and environmental stewardship will enable the country to fully meet its ambitious goals and achieve long-term impact.

While Mauritius is moving in the right direction, it is clear that much remains to be done. For businesses, the near-term priorities are clear: map CCR exposure, build a decarbonisation capex plan, access green finance instruments, and engage the Climate and Sustainability Fund with co-investable projects.

Done well, the CCR Levy will, in time, cease to be a cost of doing business, becoming instead a platform for long-term competitiveness, encouraging greener business models and positioning the country as a regional leader in sustainable growth.

--

Read the original publication at Bowmans